I don’t know any of the girls in Justine Kurland’s Girl Pictures, but it really feels like I do. Or at least, I must have seen them. Maybe they were there on the side of the highway, or in some public restroom, or just standing on a sidewalk as I passed by. The girls in their baggy jeans and bare feet. The girls in their leather boots and used sweaters. There’s something about them that feels like so many teenage girls. The images in this book weigh me down with a sense of nostalgia, and it’s not just the late nineties fashion. It’s the fact that the girls seem to be disappearing. Like catching a wild animal in a trap, it feels like by the time you look at each image of these girls you’ve already missed them. They’ve run off to someplace better or just some place that isn’t here.

Kurland started this project in 1997 when she was a graduate student at Yale. In an essay at the back of the book, she crowns Alyssum as “the first girl” to be photographed. It started as a kind of make-believe. At fifteen Alyssum had been sent to live with her dad, whom Kurland was dating at the time. While he was at work, the two women bonded and began a collaboration, merging imaginations to plot out a narrative of a teenage runaway. Kurland went on to find more make-believe runaways, but one of the images from this time seems to hold a special importance; a portrait of Alyssum takes up a full spread towards the end of the book. Perched in a cherry tree between the Hudson river and a highway, Alyssum looks back over her shoulder. The river seems to flow away, while the headlights of cars on the road seem to be approaching. With her body in profile, Alyssum doesn’t seem to follow either direction.

Adventure stories were a source of inspiration for this project. But so many of those narratives (Huckleberry Finn, Tom Sawyer, Where the Wild Things Are, The Outsiders) center around young boys. The girls in Girl Pictures plagiarize these myths until they become their own, until the original myth is hardly relevant anymore. We see worn out overalls holding onto a girl’s body by one strap in The Wall, 2000 and are only vaguely aware of Huck Finn’s similar getup because there’s something new happening here. The girl at the center of this image guides the others, looking past the camera as if it doesn’t even matter, as if the thing worth examining is actually behind us. What’s left after all this repetition of runaway legends and costumes are the common themes: rebellion, self-sufficiency, confidence. A kind of inverse of the American Dream, but with the same carrot on a string: freedom. Perhaps this is why we love runaways so much.

But of course with freedom comes the threat of danger. So many of the images in Girl Pictures were taken outside in locations that feel desolate or easy to overlook. They are often staged under bridges or beyond fences or on the sides of highways; places that feel synonymous with warnings. The privacy of the overpass is also potent with all the stories we’ve heard of women getting hurt in such places. But Kurland’s subjects never fall into those tropes of late night news or cautionary tales. In fact, even in images like Getting into Big Rig Cab,1997, where a girl looks upward, directly into the driver’s seat, from the passenger side door apparently preparing to hop in, she appears almost aggressively untouchable. Instead of looking wary, the girls seem to say “so what?” Instead of fearing danger, they get to be the source of it.

We see this as they roast pigs in The Pig Roast, 2001, and carry all kinds of dead animals in images like Roadkill, 2000, Armadillo Burial, 2001, and Twelve-Point Buck, 1999. It’s unclear whether they’ve killed these animals themselves or not, but they certainly don’t cower away from them. They are anything but harmless in photographs like Boy Torture: Hanging, 2000 where they’ve strung a boy upsidedown from a tree and approach him with sticks. Then there’s Boy Torture: Two-Headed Monster, 1999 where two girls pin a boy down and spit on him, the image captured as the weight of saliva still hangs from one girl’s lips. These “Boy Torture” images are especially playful. There’s a sense of revenge inherent in them, like they are removing the boys from this kind of narrative, asserting their roles as protagonists.

My favorite of these images is Boy Torture: Love, 1999. The focal point of the image is the back of a young girl who is raising her shirt. Instead of her face, we see the eyes of all the girls surrounding her, watching the big reveal. There’s one boy in the group, but his eyes are covered. A girl has wrapped her arms around him from behind and places her fingers over each of his eyes. It’s funny to see such an obvious removal of the male gaze, especially as it’s still present—and yet the delicate hands of a teenage girl prove capable of obstructing it. As viewers we look from his covered eyes to her watchful ones.

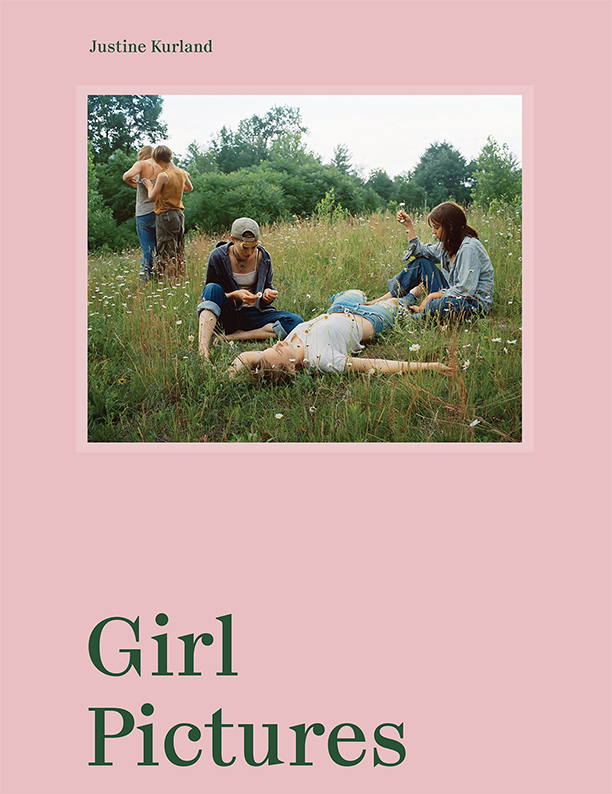

This kind of ironic playfulness repeats itself over and over again in this book. Even the title, Girl Pictures, embossed onto the powder pink cover feels vaguely tongue-in-cheek. It sounds dirty or patronizing. Just one letter shy of girly pictures, the title of this book is akin to categories like “chick lit” or “chick flicks.” I can almost hear someone critiquing these photographs as just a bunch of “girl pictures.” It makes me think of that image with the girl’s hands over the boy’s eyes again. What if rather than removing his perspective, you just take it directly from him? The title feels this way to me, like something stolen back.

Yet it feels beside the point to spend too much time considering a male perspective when looking at this project. The subjects move on, and do more interesting things. They collapse in the snow in Snow Angels, 2000, and roast marshmallows over a garbage fire in Puppy Love, Fire, 1999. It starts to feel as if they exist in their own reality, just removed enough. This is especially strong in the photographs that appear to capture two parallel worlds.

Three brunettes are eating ice cream cones in what looks to be a meadow in Dairy Queen, 2000. But just beyond the tops of the grass and above their heads, the fast food chain and a parking lot and power lines are all visible. You’d never see the girls from over there in one of those cars, but they aren’t exactly hiding either. In Guardian Angel, 1998 a girl rests against a concrete traffic barrier. She’s out of sight from the cars passing on the other side. This separation makes it seem as though the girls are escaping something, but their proximity, the recognizable world in the background of so many of Kurland’s images, suggest they might not be able to fully avoid whatever it is they are escaping. It’s still right there, pushing into the frame of the photograph. Perhaps the power of the girls in Girl Pictures lies in their ability to ignore this.

There are other things uniting all the girls in these photographs. The deeper you get into the book, the more difficult it becomes to see each girl as a distinct character. The camera stays just far enough away to keep the subjects slightly anonymous. Or perhaps it’s because they are mostly long haired, or white, or wearing similar clothing, or belonging to that vague age range that captures adolescence. Whatever it is, they begin to blend together into one visually unified group of girls. The gang picking flowers in Daisy Chain, 2000, isn’t the same as the one in Finger, 2000, but they might as well be. Kurland’s focus is less on individual girls, and more on what happens when they band together.

It’s an interesting time for this project to finally come out in book format. Twenty years have passed. All these girls are likely women now. A fact that’s oddly heartbreaking. As Kurland says in her accompanying essay, they’re “never coming back.” Spending so much time looking at these images, I’ve noticed myself looking for the girls. Driving on the highway, I peer into the trees expectantly. In bathrooms at fast food restaurants, I wonder if the lingering cigarette smoke could possibly be theirs. It’s as if Girl Pictures is a kind of fairy tale I’ve come to believe in. I guess, in 2020, I find myself wanting to imagine that there’s still a band of girls out there laughing and sticking up their middle fingers and forming a kind of intimacy that the rest of the world may never catch up to.