In my bedroom, I close my eyes and I’m free. I’m not locked in a cell the size of a closet, pieces of my mind and soul stolen with every knock on the door, privacy non-existent. With my eyes closed, I open the front door and go for a drive and laugh as loud as I want, Deborah, 49, writes to us in part in a handwritten statement under a portrait of her made by Sara Bennett.

In the image, Deborah sits on an office chair in the center of the frame, the frontality of her posture offset by her criss-crossed legs. She is in a drab-looking facility space, though its walls are plastered with images of sunflowers at dawn, babbling brooks, and icy tundra landscapes. A cherry-red cartoon smile on a stick is tacked onto the wall directly behind her. In the room adjacent, a clock is half-visible, its hour, minute, and second hands obscured by the doorframe. Incarcerated at the age of 27, Deborah is one of twenty women serving life sentences in New York State prisons photographed by Sara Bennett for the collaborative series Looking Inside.

Bennett, a former public defender, turned to photography while advocating for clemency for Judith Clark, who was serving a sentence of 75 years to life in a New York State prison. A few years into the clemency case, Bennett began photographing women who had been incarcerated with Clark while gathering testimony about her positive effects on them. Bennett produced a booklet combining the text and images, and sent it to people in and around the state government and its criminal justice system as a way to advocate for Clark’s release.

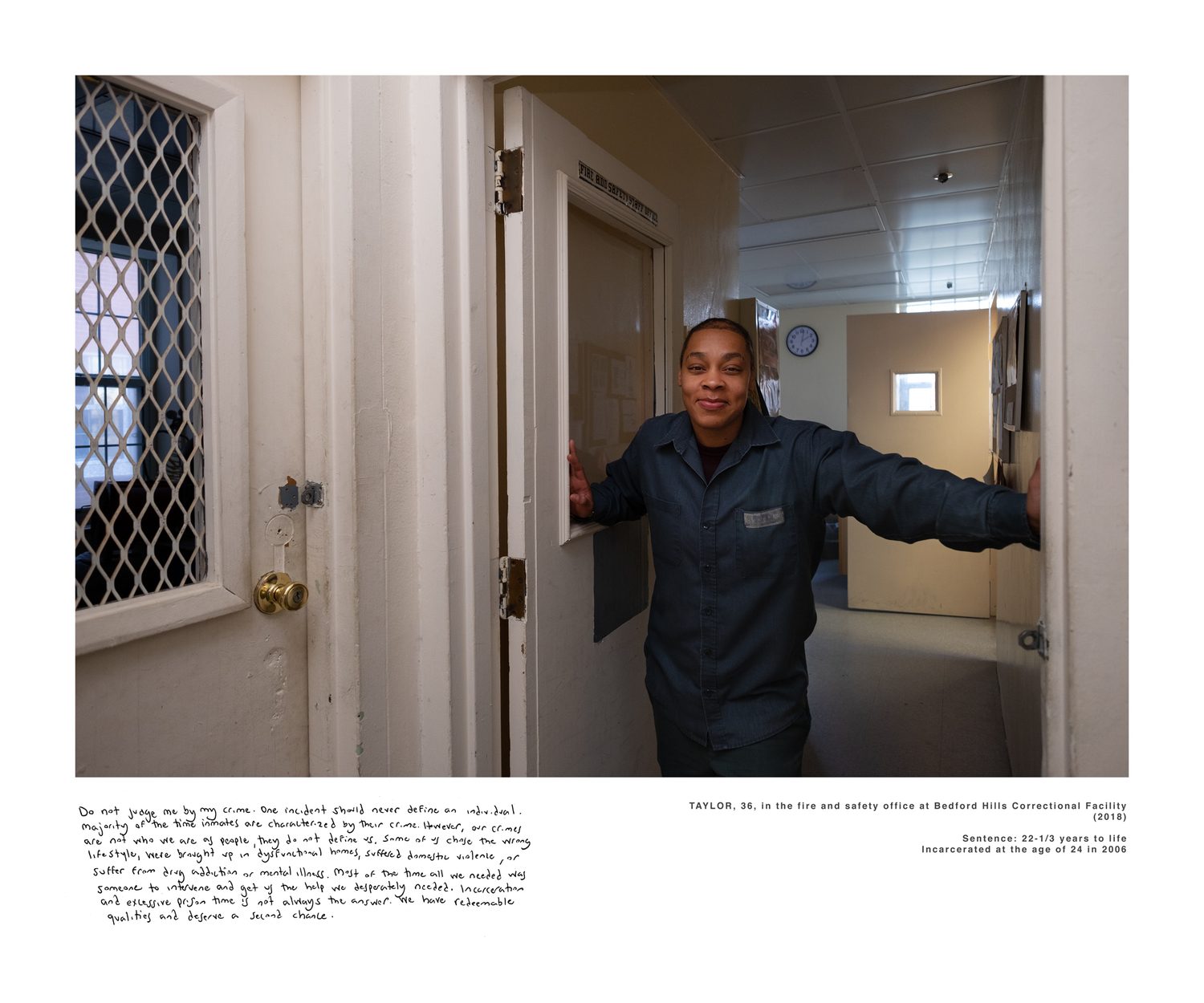

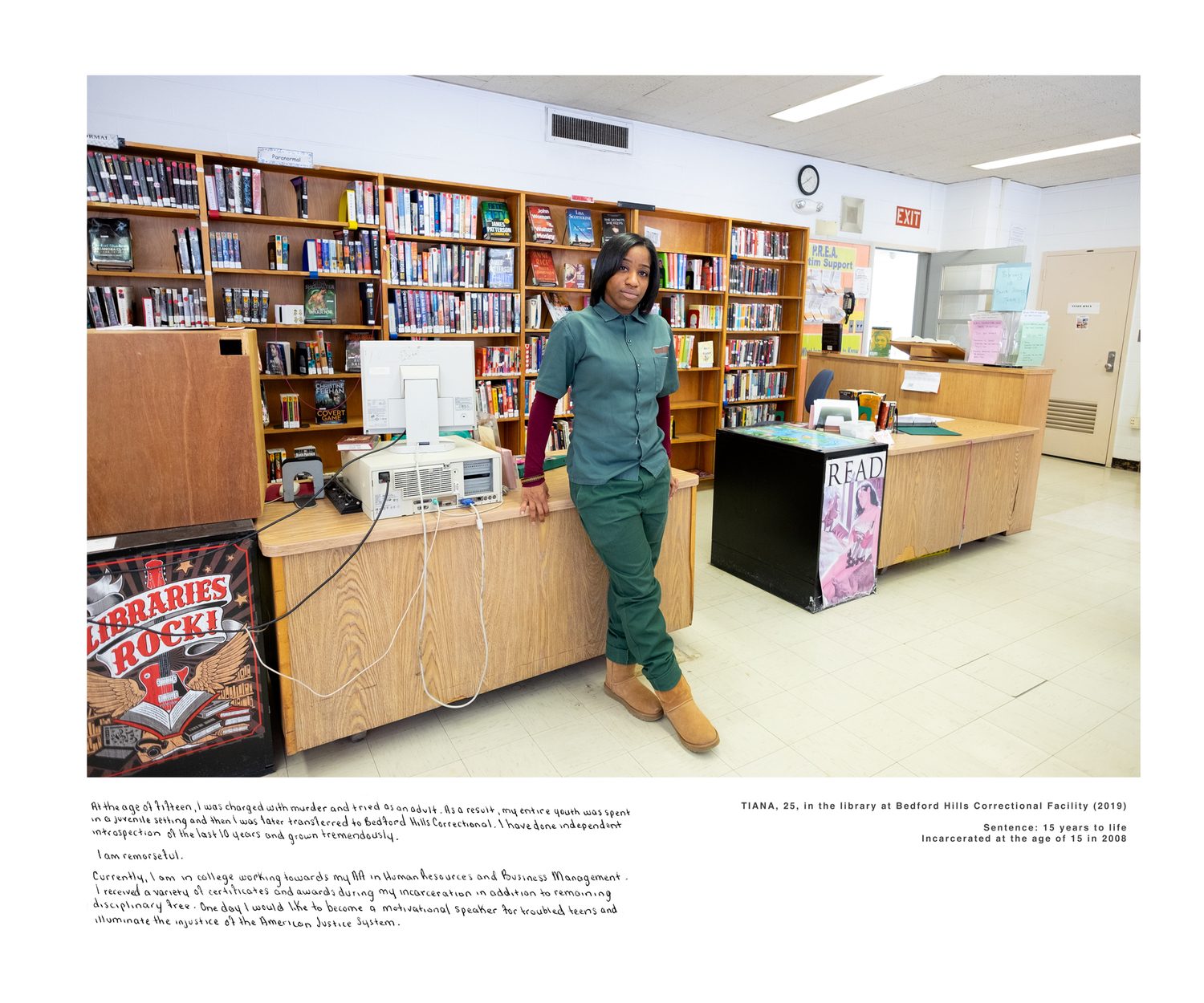

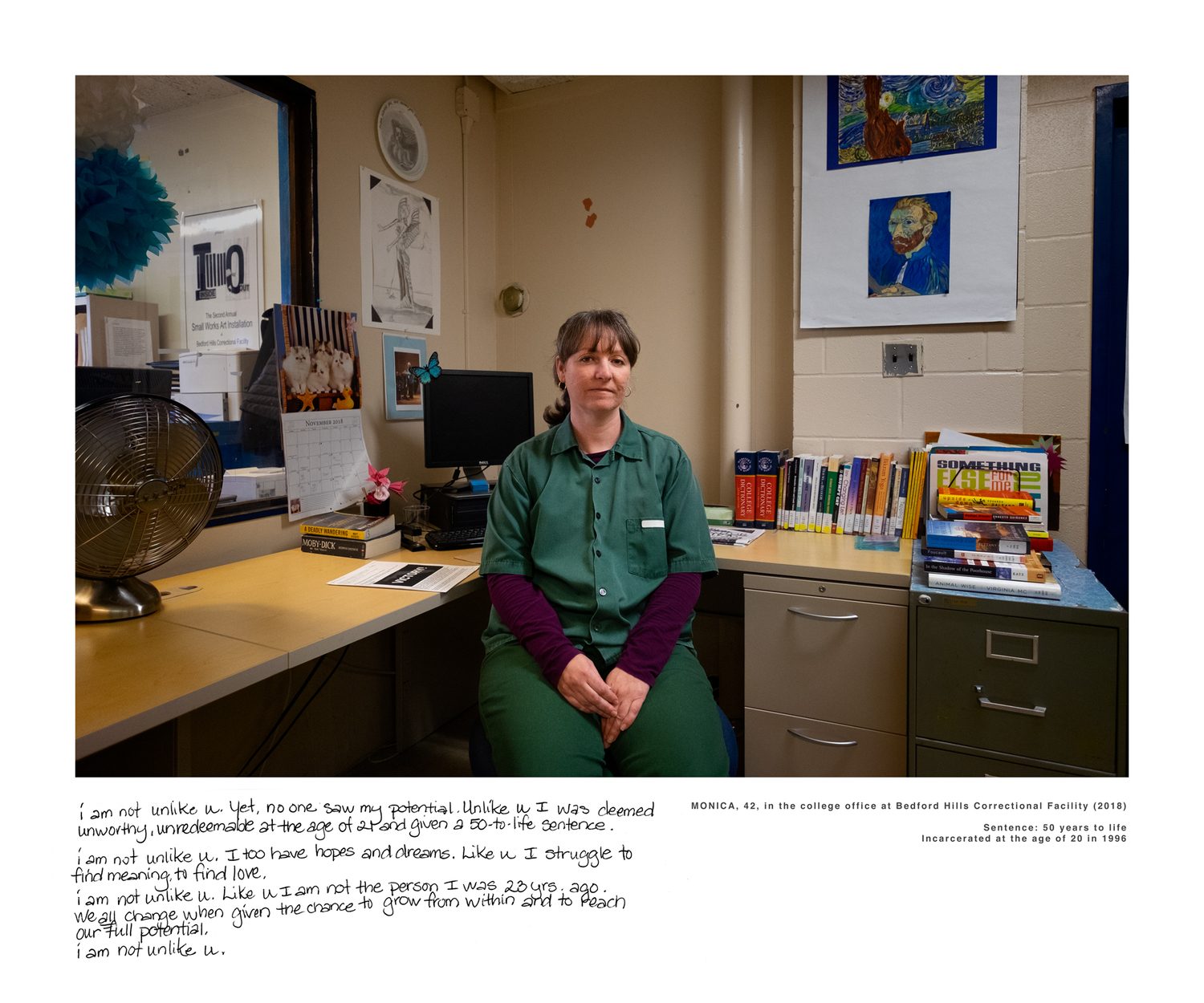

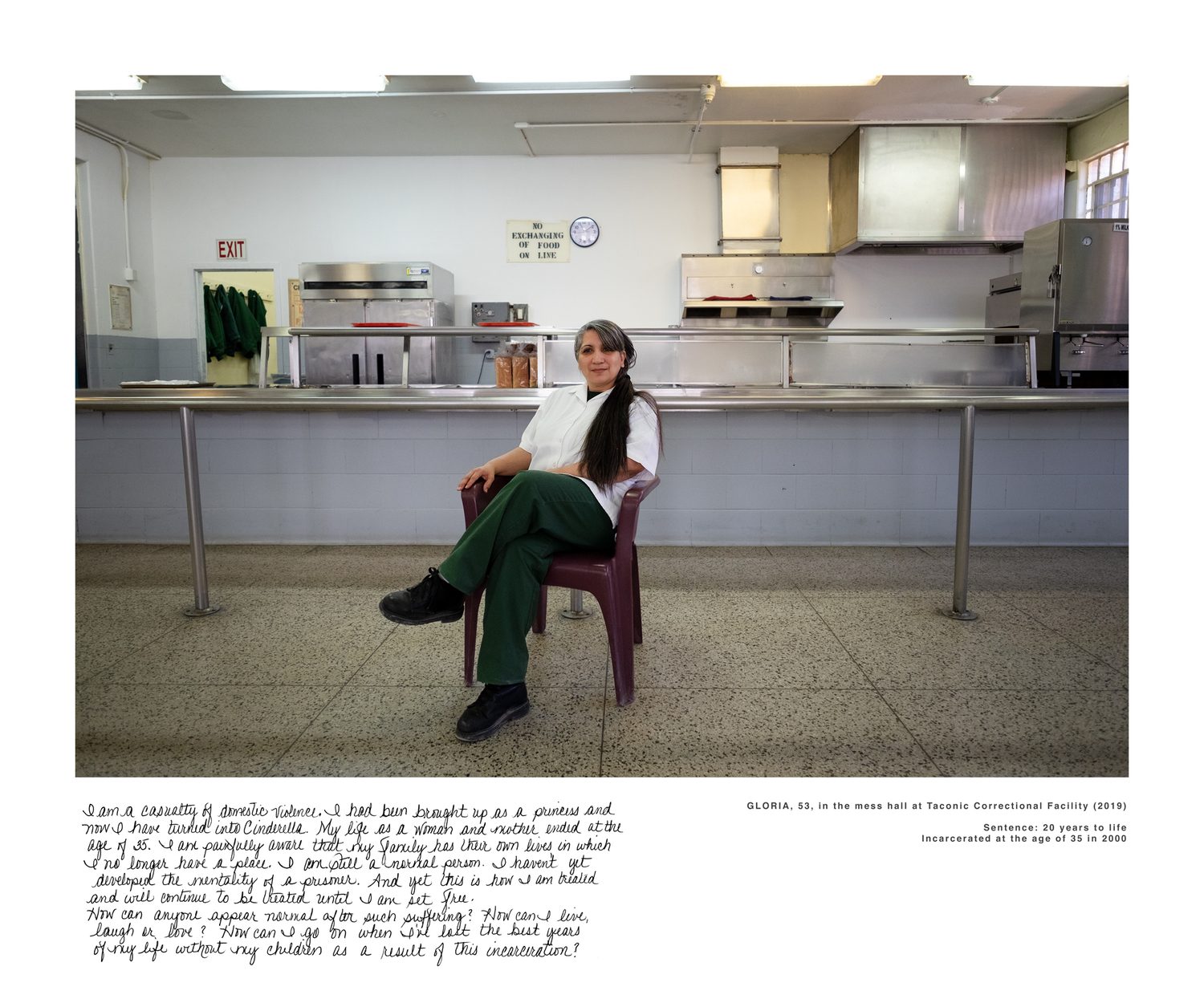

Bennett’s latest social documentary series also combines photographs with testimony. This time, Bennett employs a Jim Goldberg-esque methodology, integrating her photographic images with her subject-collaborators’ handwritten texts. “I think the handwriting draws people in,” Bennett tells me, “because you realize right away that it’s their words.” And once it draws you in, Looking Inside has an explicit goal: to advocate for the dismantling of the unjust punishments of life imprisonment in the United States.

Over the past four decades, there has been a historic rise in the use of life sentencing in the US. Today, one in nine people in US prisons is serving a life sentence, and nearly a third of these people are sentenced to life without parole. Bennett and her subject-collaborators know that America’s carceral system and the network of prisons it operates exist largely outside of the view of the general population. In this way, its mechanics and their inequities also remain largely unseen and unchecked by the public that these structures purport to have been built to serve.

There have been deep shifts in the American public’s mindset around policing and punishment over the past few years, and especially over the past few months. These have been due in no small part to what becomes visible when cameras are put in places where they did not exist before, in combination with personal testimonies. It is harder to ignore what you can see. “It’s not just police brutality, it’s also who gets arrested, and why they get arrested, and how much time they serve,” Bennett tells me, “Along with defunding police, I think we need to talk about defunding prisons.”

Instead of focusing on the macro-statistics, Bennett and her subject-collaborators shrink the issue of mass incarceration back down to human-size. The matter becomes personal. The women pictured are old, young, Black, white. They are smiling. They are sombre. Their statements are hopeful, reflexive, dejected, fearful, determined. “I hope that people really look at the photos and see human beings,” Bennett tells me, “If we did, we wouldn’t allow the kind of conditions that these women live in to exist. I think we would have to rethink everything we do around crime.”

Editor’s note: We discovered Looking Inside in the LensCulture Critics’ Choice Awards 2020. Check out the rest of the winners for more important and inspiring projects!