There’s something suffocating about a thick, white sky, isn’t there? No clouds to speak of, no hint of blue, just hazy nothingness stretching out as far as the eye can see; luminous but foreboding. It seems to arrive most often along with endless summer days, boredom and dry heat—the kind of heat we call ‘close’ and struggle to breathe or sleep in. ‘White-hot’ we call it too. Mimi Plumb’s new photobook The White Sky, harnesses the uncanny disquiet of days like this acutely.

The land as Plumb sees it is sun-bleached and suffering; its weathered cracks splitting like open wounds through the pages. The first image in the book’s main sequence is a landscape, void of people, in which the ground is a vast network of fissures. At the very end of the edit, in the penultimate picture, she presents the same scene again, but this time someone—a teenager, it appears—lies face down, eyes and ears to the ground, peering into the abyss. We’ll return to this picture later.

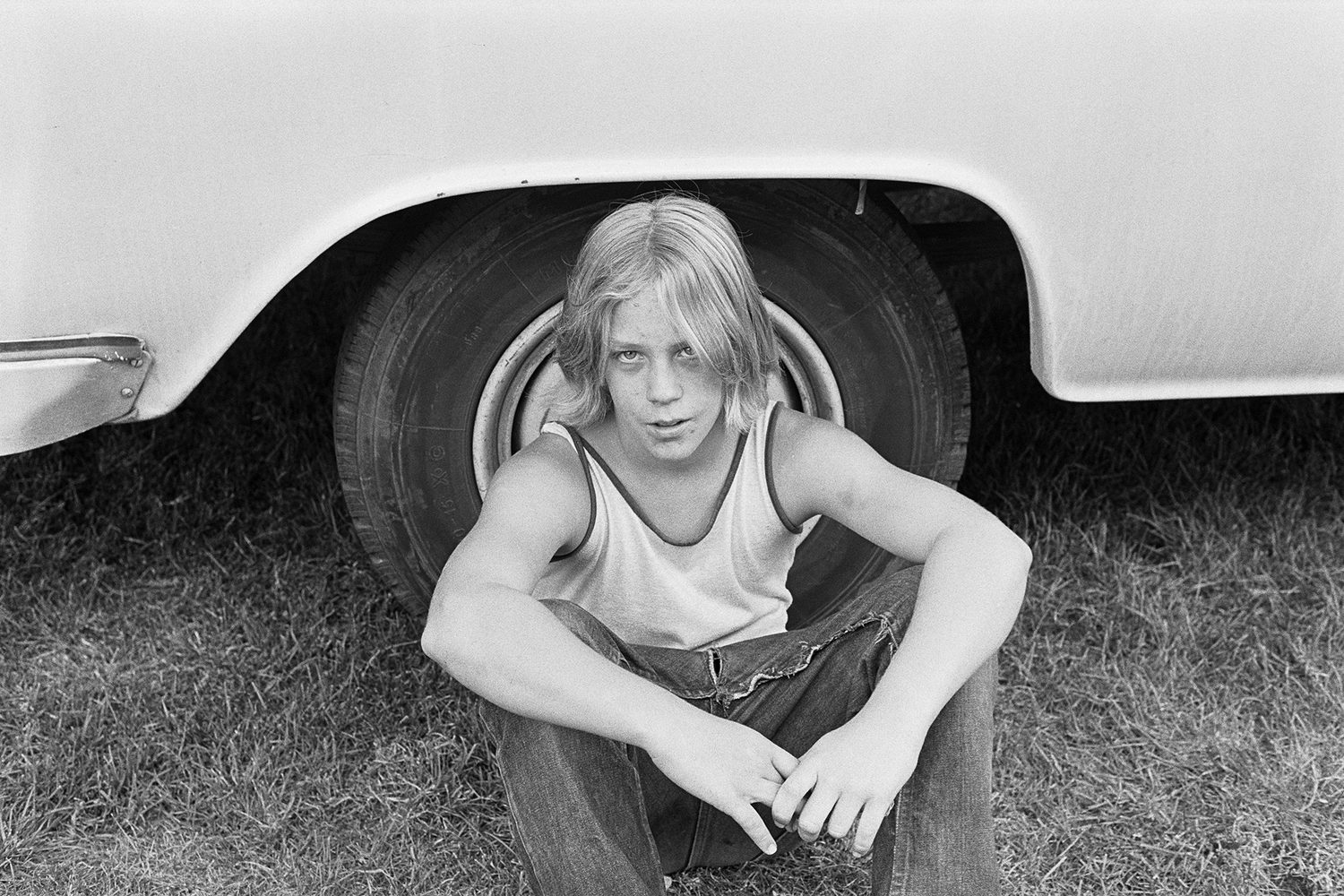

Plumb grew up in the sixties, but she returned to her small California suburb of Walnut Creek to take these pictures over several years in the 1970s. That means the kids we see here aren’t people she knew personally. But she did know what she was looking for—a commonality of experience in the way they spent their days.We can see that in how her pictures follow the rhythm and stasis of those late childhood and early teen years, pulling at the threads of the all-embracing banality of modern life.

“Modern America has been a project, an experiment,” wrote David Campany in a piece about five iconic American photobooks for Aperture magazine back in 2012. The list included Robert Frank’s The Americans, of course, as well as Joel Sternfeld’s American Prospects and Walker Evans’ American Photographs. In the same text, he went on to quote the literary critic Van Wyck Brooks who once wrote of “‘the immense, vague cloud-canopy of idealism’ that spread over the national culture in the nineteenth century.”

I couldn’t help but think of Van Wyck’s cloud-canopy as I spent time with Plumb’s book—if it was made of idealism back then, surely Plumb is telling us that now, it would be the stuff of something closer to anxiety. As the nineteenth century turned to the twentieth, that ruthless sprint towards national idealism gradually morphed into a sort of disaffected inertia for many, and by the time the 1960s rolled around, feelings of frustration and alienation were spreading. “I watched the rolling hills and valleys mushroom with tract homes and strip malls, and to me and my teenage friends, they were the blandest, saddest homes in the world,” said Plumb recently. She was always, she says, “looking for stuff to do” and “ a place to hide from the bright, white sky.”

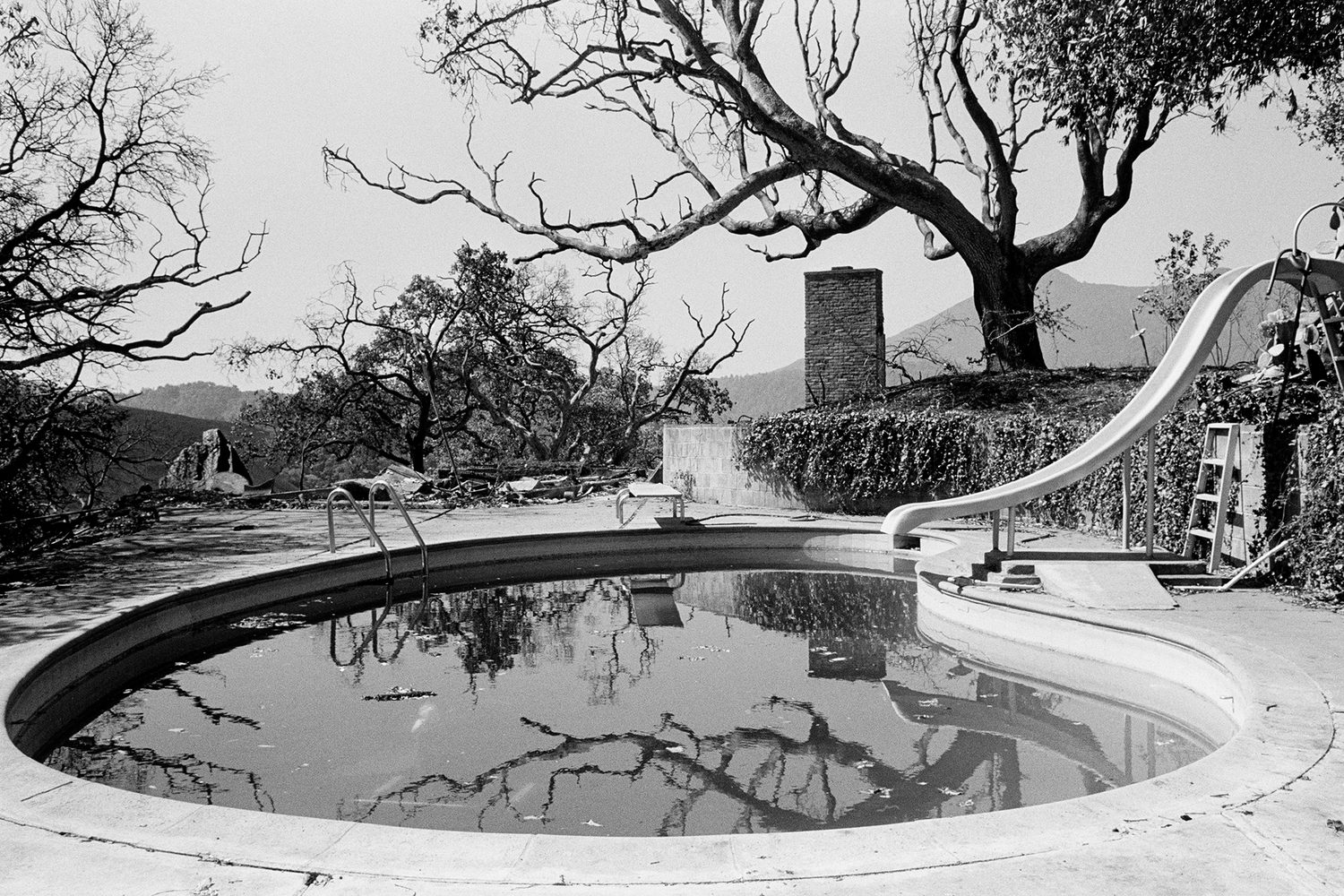

There’s a tangible weight to the pictures in this project that manifests as a sort of constricted anticipation in book form, slowly unfurling across the pages in scenes of rolling plumes of smoke, dogs baring teeth behind gates and swimming pools so eerily still they look like glass.

An introductory sequence of images comes first, punctuated with the title split word-by-word—bold white text on pitch black page, and the photographs sandwiching those words are key to understanding the whole narrative arc of the publication. After ‘THE’ comes an image of a little boy, shirtless and standing atop a rock on tiptoes, wild arms outstretched towards a gathering storm. Then comes ‘WHITE’, and after it an image of more people gathered; a cluster of adults this time, outside of a shopping mall, necks craned skywards, eyes squinting, hands casting shadows across faces. Lastly, ‘SKY’, followed by two people driving out from a gas station, faces almost entirely eclipsed.

The blurb of the book refers to “a world in which an unknown trauma hangs heavy in the air, and children rule the roost” and it’s true that a glimmer of lawlessness emerges across its pages—kids run feral in tire piles, hang out on graves, learn how to shoot rifles. It’s as if they’re fending off those first vestiges of adulthood, and the effect of this creates a vague, almost ‘Lord of the Flies’ style narrative, if Golding’s novel were to be transported to the backyards and model homes of small town suburbia.

People congregate in Plumb’s pictures, in twos, and threes and fives, and sometimes in huge crowds. In fact, the three opening images are of swarms—of cars, and then of people, covering land like ants. These are inhabited images, and it is nearly always the human presence that defines them; the rhythm of our activity and inactivity. Architecture, on the other hand, is a weirdly fractured part of the story—houses are almost always seen completely isolated within their surroundings, and separated from the viewer through swathes of black leaves or huge piles of dry earth.

Plumb acknowledges that California is a place that has always loomed large in the cultural imagination, but she does this while simultaneously letting us know that for her it was still monotonous to grow up there. She includes images of the same symbols that have always enticed outsiders to the territory—the abandoned movie theatres, the burned out cars, the charred ‘ghost town’ aesthetic—but what is perhaps most compelling about her vision is how she then transforms some of those cliches into new forms. The Hells Angels motorcycle is reduced to toy-size and played with by a little boy, for instance, while cowboys are rendered mere cosplay in halloween costumes worn by kids.

Let’s return to that picture of a teenager lying upon the weathered earth. What this scene confirms is a feeling that brews throughout the book; that there are two intertwining stories being told in The White Sky—one of the territory’s ecological decline, and one of the stifled coming-of-age of its young inhabitants. The things that change rapidly and the things that never seem to change at all. This is a book of allusions, and layered social commentary; a book of land and people. Perhaps then, in this sense, we can say that it is ultimately a book about time. Specifically, the way lives unfold against the environmental time of a place like California; with its fires and its droughts constantly reshaping its bones. The book closes with an image of the open road; there as always but changed now, at least in our view of it. How could it not be?