“It was probably around 1994, a difficult time,” says Guram Tsibakhashvili, “when my friend Boris Shaverdiani, also a photographer, thought that he didn’t have any reasons left to stay in Georgia and decided to emigrate.” Shaverdiani worked at the Institute of Physics, which also operated a small photography lab. On the eve of his departure, he informed his friend that someone had left a suitcase of anonymous negatives in the lab.

“He told me to take a look because the suitcase would surely be tossed out,” Tsibakhashvili recalls. So it is almost by chance that the Georgian photographer, artist and educator, brought home the suitcase of negatives, becoming the custodian of this extraordinary collection of approximately 4,000 negatives; the life of another unique photographer whose work might have otherwise been lost to time. 4,000 negatives that constitute in their entirety a comprehensive archive of Georgia under Soviet rule, creating an alternative take on history that wasn’t just the succession of political events but rather an impression of everyday life.

To anyone else, the negatives might at first have appeared to be an ordinary family album. Tsibakhashvili, however, is somewhat of a maverick of Georgian photography. Educated as a chemist, he started—in his own words—as an amateur, before working as a photojournalist, then shifting towards a more conceptual approach. His own archive of documentary photographs spans the history of post-independent Georgia so far. He has also tutored an entire generation that are starting to emerge as photographers in their own right. In other words, here was a photographer looking at the world through the eyes of another, recognizing not only a sophisticated technique, but also a distinct way of looking at the world.

Going through some four decades worth of photographs, patterns begin to surface; style, composition and subject matter, but also certain faces that appear and disappear, emerge in photographs evidently taken several years later and then don’t appear again. It is easy to see them now, when the negatives have been digitized, but it would have been a gargantuan task to go through all the photographs, especially in the mid-1990s, when practically no digital negative scanners were available in the country, and each print would have to be made individually. Nevertheless, Tsibakhashvili started making prints from the archive.

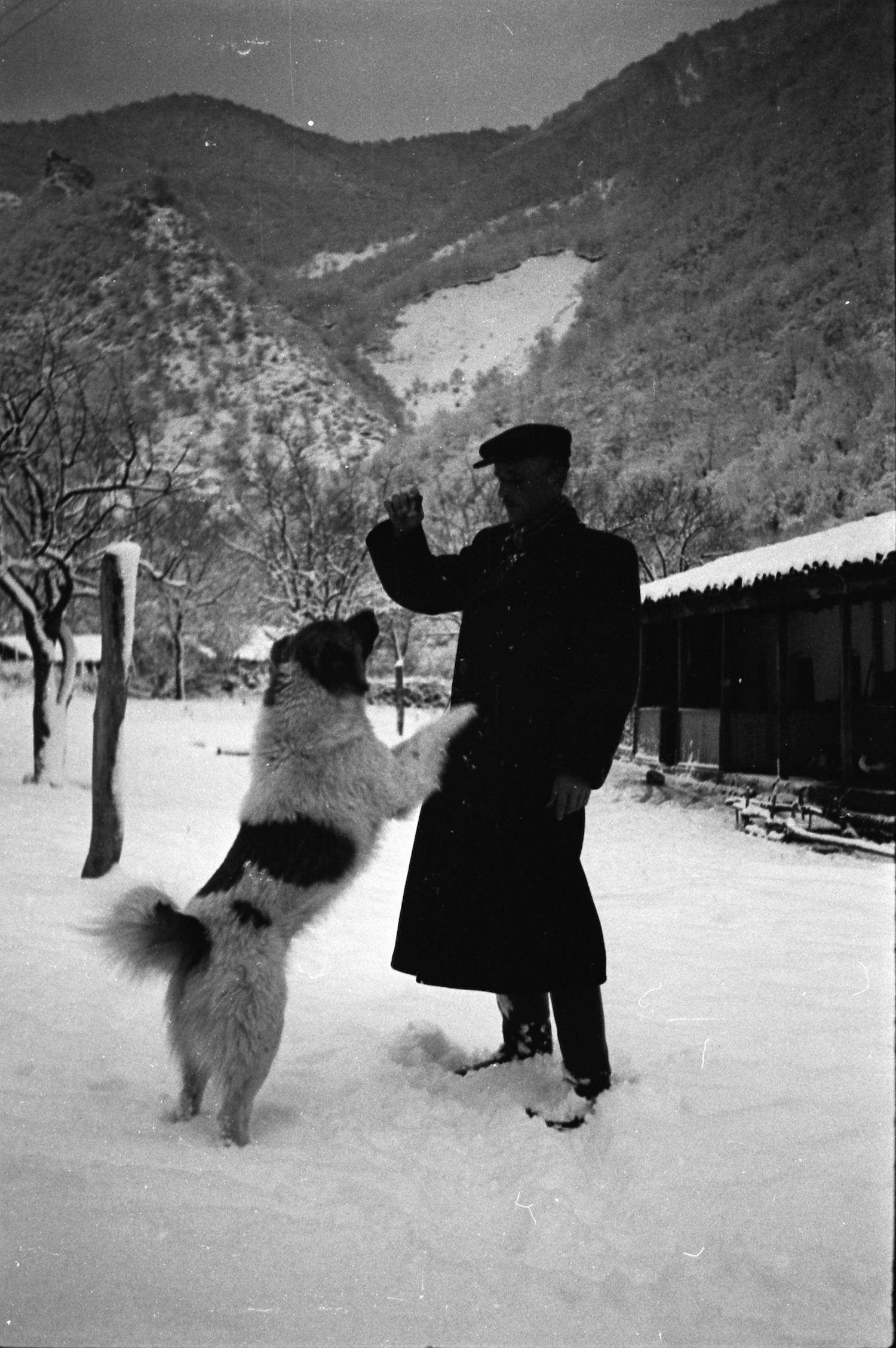

“It took me around a year of wading through the negatives to find the face of the photographer himself,”he says. The face was located in the earliest photographs; youthful, playful self-portraits, sometimes taken in the mirror, at other times, evidently with a shutter-release or a timer. Over the generational span of the archive, ranging from somewhere around the end of World War 2 through the early 1980s, both his youth and the frequency of his self-portraits fade, but the playfulness does not.

It is precisely this playfulness that sets these photographs apart from rigid, state-sanctioned Soviet photography that left hardly any space for anything but propaganda. Filling this memory-hole with spontaneous images of family and friends, ID photos and portraits, insignificant and special events, work and vacations, the contents of the suitcase sketched out a rich and full life in a complicated era. “I don’t think there are many photo collections in the former Soviet Union that were made by ordinary citizens, and not, for example, journalists,” says Tsibakhashvili. Yet the identity of the man in the mirror remained a question mark.

At first, Tsibakhashvili showed these images to other Georgian photographers. The community is small enough that someone must have recognized the face, or even the style of a fellow photographer. But none of them did, and the mystery of the photographer’s identity only deepened. Tsibakhashvili would use some of the photographs, especially the self-portraits, in his own conceptual works, expecting someone to eventually come forward. But no-one did, for almost a decade.

Finally, a breakthrough came in 2001, when an advertising company offered him a billboard to display an image around the deliberately vague and general theme of ‘Tbilisi Life’. Realizing his opportunity to solve the mystery, Tsibakhashvili used one of the group portraits from the archive, a characteristic Tbilisi scene of friends hanging out. Three days later, someone called the advertising company, then reached out to Tsibakhashvili himself. She was one of the people in the photo, she said, and the photographer was her uncle. The man in the mirror finally had a name: Rezo Kezeli.

Details about Kezeli started to fall into place, and so did the narrative of his life. He was born in 1925 and passed away in 1988. His father was a military officer, a stately gentleman who often appears in photographs in uniform. His mother, featuring in many solitary portraits, was a homemaker. Images of his parents are both joyous and melancholy. He grew up in Tbilisi, in a house facing a communal yard, where he often helped his neighbors by photographing them for their ID photos. In his family apartment, he would photograph dinner parties. He married and had two kids, who, unlike most of his subjects, often appear in color photographs. After he passed, and the USSR fell apart, his immediate family emigrated out of Georgia. It is not known how the suitcase of photographs ended up at the Institute of Physics.

Sometime in the mid-1950s, Kezeli’s passion for photography transformed into his profession as a television camera operator. In 1977, he even directed a short film. Kezeli would take his camera on work trips, and sometimes even make screen tests through photographs, as he did for the auditions for the earliest Georgian television newscasters. His behind-the-scenes photographs taken on television assignments carry considerable historical weight, documenting visits of foreign celebrities or political dignitaries, but also offering a glimpse of everyday life in places where he was sent from work. Nevertheless, photography always remained a separate pursuit from his work, a leisurely activity. “Most of his photos he took during what was his private time,” Tsibakhashvili says. In other words, he remained an amateur.

This is not to doubt his proficiency as a photographer. Far from it, Kezeli’s style was more inventive and original than those of ‘official’ Soviet photographers of his era, whose photographs stayed well within the ideological lines dictated by the state. Kezeli’s television job too, would have called for a certain rigidity of style among these same ideological lines. “I don’t know how it was elsewhere,” Tsibakhashvili says, “but in Georgia, if something came from television, it was as if it came from the Bible—unquestionable truth.” Private photography seemed to offer Kezeli a different way of making images, without any editorial guidelines or intervention, allowing for levity and self-expression.

Like in so many other languages, the Georgian word for amateur (მოყვარული, mok’varuli) has etymological roots in the word for love (სიყვარული, sik’varuli), and Kezeli’s love for photography is also love through photography. His photography is a document of love towards his family in the tender images of his parents, wife, and children.

It is a document of a life-long fascination with cars. It is a document of vacations in the countryside, away from the business of urban life. It is a document of the joy of eating, drinking and hanging out with your friends, of life in the city, of being in nature, of looking at animals, of travelling by train, of watching a train pass by, of playing an accordion. And even though all of this was so long ago, it is the evidence that—as Tsibakhashvili puts it—in whichever age they live in, “every individual wants to be happy, no matter what kind of ideological pressure they might be under. This kind of photography is an attempt to build subjective joy within your own frame. You can be happy with whatever you might have, like Diogenes in his barrel.”

At the moment, the only way to access the archive is through Tsibakhashvili himself. “The culture of photography books is relatively young in Georgia, but I hope one day we’ll be able to publish these as a book.” If everything goes according to plan, there might be a large retrospective of Georgian photographers at Arles and where Kezeli’s photos will feature prominently.

Like with every other private archive made public, there’s a slight feeling of intrusion when looking at the photographs. Kezeli never set out to create a photographic archive per se, and the suitcase of negatives is still a family album. Looking at the photographs, sometimes I feel like an accidental guest at a dinner party. Would Kezeli himself appreciate the newfound attention that is only growing some 35 years after his passing?

Some time ago, I had the opportunity to pose this question to Kezeli’s nephew, Archil Kezeli, a prominent ophthalmologist who appears in the photographs as a young boy. He pointed out the accordion that appears so often in the photographs and told me a story. When his uncle was a young man after World War 2, a crew of German prisoners-of-war were made to work as builders near his house. One of them overheard Kezeli playing the accordion and ventured into the yard that appears so often in the photographs. Overcoming the language barrier undoubtedly with gestures, he explained that the sound of the accordion reminded him of home, so Kezeli played for him, and the man wept. “That is the kind of man my uncle was,” Archil said, now himself an old man. “A very, very generous man.”