Since its first iteration in 1985, New Photography has always been a banner exhibition for MoMA. A long running group show that brings together multiple photographers around a set of themes or methods of working, the annual event both reflects the currents running through contemporary photography and, to some degree, the world at large. 2020 presented its own difficulties as museums worldwide were faced with the challenge of operating amidst a pandemic. How does one mount an exhibition in a time of overwhelming uncertainty?

The answer in this instance was to move fully online, much as the rest of the world has. In Companion Pieces, the curators have chosen to both fully embrace and shake up the online format, giving voice to the participating photographers. Over the course of the exhibition, each week the work of a different artist was introduced through the museum’s online Magazine platform. In this regard, the online format was used not simply as a slideshow, or a replica of what a viewer would have seen in the physical exhibition, but as a deeper, multimedia look into each artists’ practice.

The featured artists hail from a range of locations and backgrounds, creating a broad, thriving set of conversations and crossovers. The artists include David Alekhuogie (American, born 1986), Özlem Altın (Turkish and German, born 1977), Maria Antelman (Greek, born 1971), Iñaki Bonillas (Mexican, born 1981), Sohrab Hura (Indian, born 1981), Dionne Lee (American, born 1988), Zora J Murff (American, born 1987), and Irina Rozovsky (American, born in Russia, 1981).

In an extended year of isolation, Companion Pieces asks questions of communication—how do images speak to one another, and beyond? One of the foundational tensions of photography, this question takes on a renewed urgency in light of recent events. The notion of connection and exchange feels both ever more relevant and at times just out of reach.

Questions encompassing mark-making, archives, framing, growth, and violence course through these artists’ work—and like all good questions, they do not offer easy answers but rather ask for true thought and reflection.

Complicating a singular reading of the image is a gesture that runs through several of the projects on view. The work of the California-based artist Dionne Lee speaks of her interest in landscape photography and history, and questions of authorship. At large, the images question who has historically captured the landscapes that we see and asks what that vision has been used for.

In manipulating images either in the darkroom or after the fact the interjection of her own mark-making shifts the narrative. There is an ambiguous nature to the photographs; it can be hard to discern what has been found, what has been made, further manipulating and reframing photographic narratives. In her section of the exhibition, Lee speaks of her interest in the natural world and how to relate to it, exploring an unease that is framed by experiences of ancestral trauma juxtaposed against the sense of the landscape as a refuge. The two sides of this relationship suffuses the work on view, as Lee says, “holding those two truths at once,” allowing her to renegotiate her own understanding of these spaces.

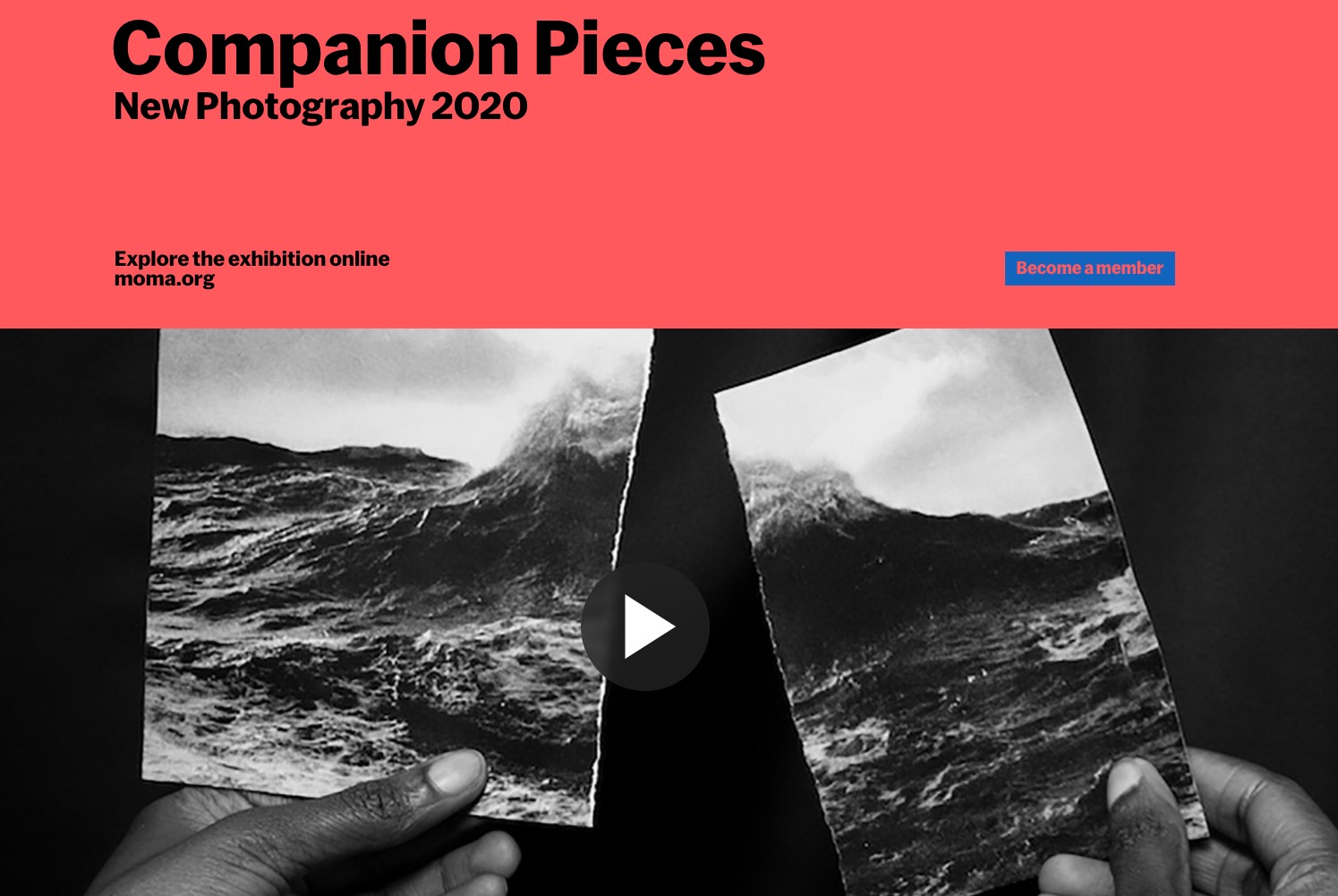

In the video Drafts, the viewer watches from overhead as Lee lays out image after image, layering, ripping, removing, adjusting repeatedly. The notion of an image as something static, fixed, is repeatedly dismantled. In the image Breaking Wave, two hands hold an image torn in two of a wave breaking. Has the wave broken or is it breaking? How we perceive aspiration, freedom, and the connection to survival surfaces within Lee’s work.

In True North, a collage of silver gelatin pieces, the hands are used as a tool to navigate across time. In speaking of this work, Lee describes the gesture of arms outstretched, hands forming a W, as one used to measure the sky and locate the north star; a way to guide oneself, but also as a reflection on a gesture perhaps used by people fleeing enslavement. The act of making the measurement that one’s ancestors may have made connects across space and experience.

Investigating the intersecting layers that lie beneath the surface of the present, Zora J Murff’s work At No Point in Between documents the historically Black neighborhood of North Omaha, Nebraska, questioning social structures, injustice, anti-Black violence in America and the role photography has played through it all. A mixture of quiet landscapes charged with an underlying violence, and tender portraits, the project deals with the legacies of racist policies that continue to act upon people and places today. Found images and objects, such as a graduation photograph, round out the work to show, poignantly, the persistence and celebration of Black life against these oppressive structures.

Scattered throughout the artist’s page in the online exhibition, audio excerpts invite the viewer further into Murff’s process of making, as well as the history of the work. In one audio snippet, Murff describes the process of making the portrait Chris (talking about fear) and how letting the conversation lead allowed the space of the image to emerge. As the two spoke about fear and what it means to be a Black man in America, a moment of brushing something out of an eye became a gesture that resonated.

In David Alekhuogie’s work, the body itself is treated as a landscape, providing a framing device to explore the ways in which it has been objectified, bringing to focus its minutiae. In the series Pull Ups, the artist, working in his native Los Angeles, took photographs of a closely cropped Black male body. The images at first become color fields, but with time the detail of fabric, waistlines, hips come to the fore, pushing away at the abstraction of the image and instead bringing up questions of the body—specifically the conflicting ways in which desire and politics have been forced upon Black male bodies.

In his audio introduction to the work, Alekhuogie speaks of the images disarming the idea of the low-slung pant as a signifier of danger, and instead framing it as a portal into the complexity of our society’s desires. In pieces such as Target, the original images are photographed, placed within the landscape of LA and rephotographed. The locations were the sites that held either personal or historical resonance. The resulting layering creates a mapping of history, relationships, pattern.

Collage features in the work of several of the artists; an act that dislocates images from their original meaning in order to speak and move anew.

Marginalia is the title of Iñaki Bonillas’ featured series, culled from books that act as a catalyst for a new journey. In his audio introduction, Bonillas refers to himself as an attic photographer; someone attuned to residues and archives.

As a self taught artist, he has used his library for source material for the collages included in the exhibition. In another clip, the artist speaks of the underlines and marginalia of his father’s books and how they have acted as a means of conversation with a figure who has since passed on. This is another rich example of what is so special about Companion Pieces; we are experiencing both an exhibition and, in a way, a series of studio visits, in which the artist speaks to the viewer directly.

The white border of images taken from books becomes a path that leads the viewer through the work, entering on the left and making sharp turns as if walking down a street of imagery. In Marginalia 7, images of sculptures from museum catalogues make up the collage, which in effect is a history of sculpture over twenty centuries, unfolding across the piece, spanning from an early Greek sculpture on the left to a piece from the twenty-first century.

A process of becoming threads the montage work of Özlem Altın together. Layers of paint over long, photographic collaged prints explore the body, birth, death, and growth. Using imagery found through natural history museums as well as ones made or staged for the work, Altın, explores the mapping or materialization of time. The human body, in different positions and states, is combined with animals and archaeological patterns, creating hybrid organisms and the intertwining of dependency.

In the works of Irina Rozovsky and Maria Antelman, frames create the means of distorting visual space and memory, leaving gaps for our imagination to fill. Rozovsky’s small keepsake frames juxtapose time, creating possible narratives out of the combination of image and antique frame. For Antelman, the frame disrupts the body inviting us to piece together and connect its fragments ourselves. In Hall of Mirrors, she speaks of the body as a tool; the eye functions as a mirror as well as a camera. Each limb becomes heightened in its function.

By contrast, Sohrab Hura places two series—made in different locations during opposing seasons—in dialogue with one another. In the project Snow, he looks at the dualities of Kashmir, whose disputed territorial status has led to multiple wars between India and Pakistan since the 1947 Partition. The passage of time reveals not only the beauty of Kashmir but also the inescapable signs of conflict. The images depict the everyday-ness of violence and sacrifice, the icy stream tinged with blood, the blackened trees along the side of a road. The photographs are not overly graphic, they never yell for attention. Rather than telling, he uses listening as a starting point.

In Song of Sparrows in a Hundred Days of Summer, heat, stillness and the anticipation of the monsoon season animates the images. The languorous hands brushing a bare back, the sliver of an eye gazing out of a mirror, a child’s face emerging from thick, brown water speak to the type of atmospheric conditions that influence emotional conditions.

Questions encompassing mark-making, archives, framing, growth, and violence course through these artists’ work—and like all good questions, they do not offer easy answers but rather ask for true thought and reflection. The exhibition’s title hints at this from the start; Companion Pieces becomes more than a set of images on the screen.

At this particular moment in time, companionship seems ever more necessary, important, and at times at risk. Photography in this way can help fill the void, the photograph of a companion as looked to for comfort, the photograph sent to a companion as means of connection, and the photograph itself as a fellow traveler, a companion in conversation.

Editor’s note: Companion Pieces was organized by Lucy Gallun, Associate Curator, Department of Photography and can be visited online.