In the summer of 1936, the British artist Eileen Agar found herself on the coast of Brittany, France, staring up at a gathering of rocks in the tiny port village of Ploumanac’h. It was mid-July, warm, and she’d travelled there for a holiday. Stomping around the site, weaving and looping herself between gaps in the formations, she was awed by their presence, writing later how she’d seen “the most fantastic rocks” that day, like nothing ever before.

“They lay like enormous prehistoric monsters sleeping on the turf above the sea,” she continued, and gave them names like “Rockface”. A decade after this, in 1948, the poet W.H. Auden wrote In Praise of Limestone—his most famous of allegories for the human body, purporting that the most human of landscapes could only be a rocky one.“‘When I try to imagine a faultless love,” he wrote, “Or the life to come, what I hear is the murmur / Of underground streams, what I see is a limestone landscape.”

All this anthropomorphic personification of the geological world isn’t new or unique to Agar, or Auden, of course. But on reflection, it makes one wonder about the human relationship to the natural world, and about what we do to the environment when we make attempts to contain it, wrap it up in human history, or bend it towards our understanding by giving it character and shape and story.

This fascination is an instinctual, sensory one that often eludes language. From a young age, we collect things from the natural world—rocks, shells, leaves, flowers—and we admire them because they teach us scale and perspective, the history of the earth, growth and death. But we also love them because they are our chance to own a slice of nature, hold it in our hands, and take it home. Every rock has its own origin story, of course—where it came from, the way the earth shaped it across centuries—but for many of us humans, a rock’s second story—what we might call its emotional story—starts when we pick it up.

Our relationship to the natural world is an elastic, multifaceted and ever-changing entanglement that artists across time have grappled with. Today, an unavoidable sense of impending ecological crisis pulses under our daily lives, and in recent years a number of photographers have made projects that respond to that anxiety. Coming together to form a new and more urgent environmental gaze, several of those artists are included in this essay. Both directly and indirectly, they find ways to interrogate the longevity of our increasingly fraught relationship with the natural world—through the subject of rocks.

For Chinese artist Feiyi Wen, the shared emotional and cultural histories laced into the land appeal to her most. Taking her own photographs of landscapes, as well as working with found and archival images, she consistently returns to pictures of rocks. In her project Under the Yuzu Tree, she riffs on the nature of memory in an atmospheric way by using different papers and techniques. Where some images of stones fade close to complete darkness, others are so pale they are almost invisible. In this way, solid objects like rocks become spectral and translucent, reminding us of our precarious relationship with the natural world as it changes and disappears.

“In my work I refer to some examples of material culture in early China and Japan, including decorative objects and artefacts. I understand them as compressed miniature forms of landscape, and in fact, I consider the historicized emotions embedded within these objects,” she says. “The appreciation of rocks has a long history both in China and Japan, and the idea in these cultures is to take naturally occurring rocks and display them, usually in gardens, for appreciation purposes. I am much intrigued by traditional practices such as these. They are designed to welcome nature inside to the interior, to embrace nature in the least disrupted way.”

What she is trying to do with this work, is create “an in-between place to contemplate, reflect and feel” and populating her images with symbolically-charged objects such as rocks helps her do this. There are several layers to her encounter with natural imagery, she says, and “rather than simply taking the fragments from the landscape, it is more like a two-way conversation. I see landscape not just as a theme or a motif, but also as a medium and a method.” A key aim of Wen’s, then, is to enter into a dialogue with the landscape—to see what it can tell her—through the language of photography.

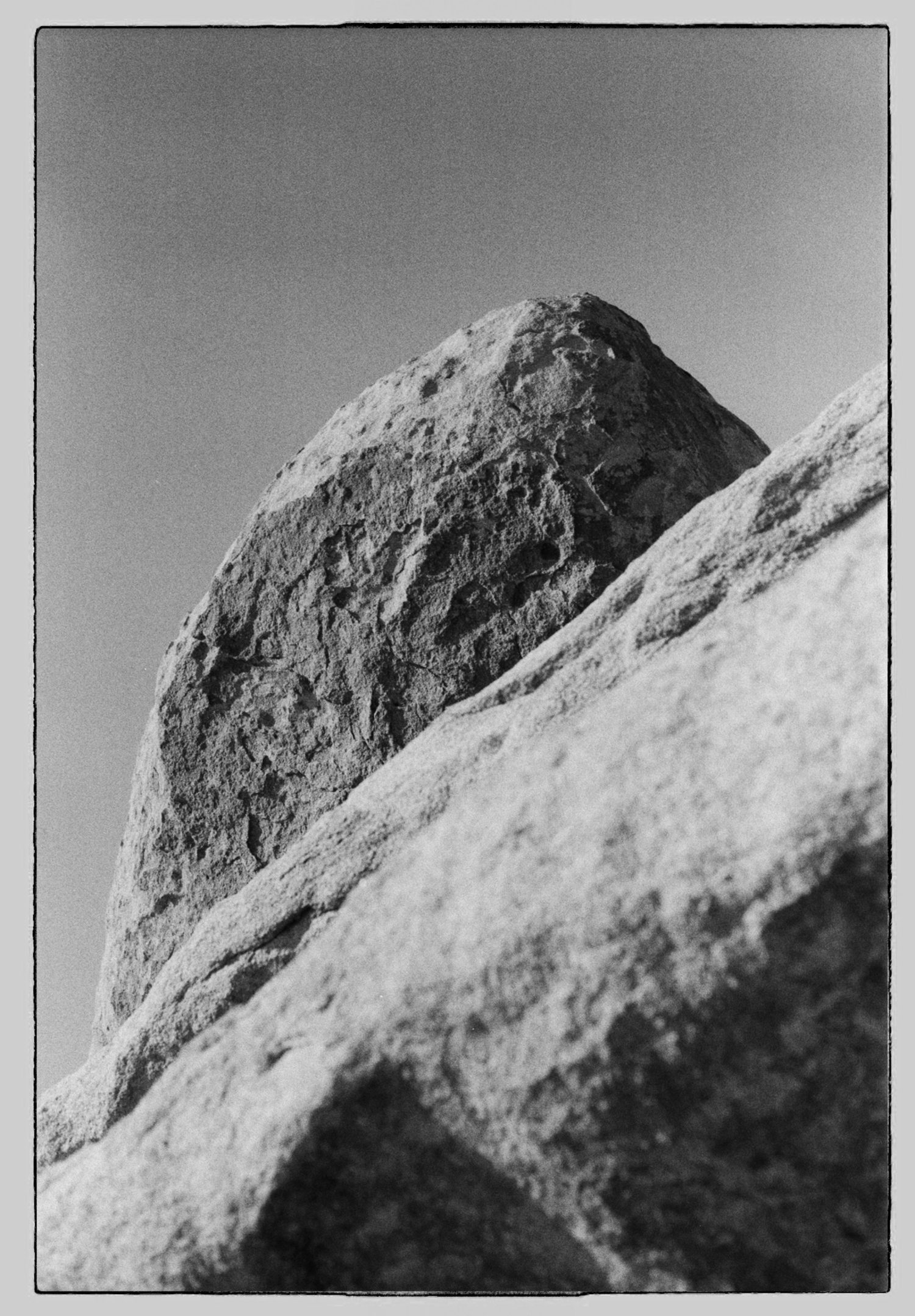

London-based photographer Elena Cremona shares this philosophy. In her project, Postcards from the Past, she documents the rocks of Joshua Tree, honing in on the creeping splits in their surfaces to reflect her own wounded emotional state at the time. “For me, it’s about being aware that we are a part of nature—rather than apart from it—and that by finding small connections with it, like picking up a rock, we can understand where we’ve come from and how we’ve developed,” she explains.

“I think rocks can teach us everything about the environment, in every state. If you wet a rock, for instance, a further composition is revealed. You can see the development throughout the years in the colours and sediments. And we can even reconstruct a picture of the history of the territory the rocks came from by studying the dirt that is attached to it. Nature is still in the making. We follow fragmentary records of the past by examining rocks in the light of the present.” For Cremona, landscapes are terrains of possibility, and nature is forever in a state of ‘becoming’; a process that happens with or without our presence.

Emotional weight is central to American artist Ryan Thompson’s photobook Bad Luck, Hot Rocks too, though in this work it manifests more as a moral lesson, or a visual fable warning of the consequences of removing things from their natural surroundings. After visiting the Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona a few years ago, Thompson was bowled over by a small display of ‘conscience letters’ at the park’s museum—a collection of correspondence named as such because they were all sent to the park by previous visitors, along with rocks they had stolen and were returning.

Some return them out of guilt, while others say the rocks cause bad luck, with the most extreme letters telling of people dying or great sums of money being lost since the rocks were in their possession. The park also had a ‘conscience pile’—the place where all returned rocks were deposited. Thompson returned the following summer with a collaborator, Philip Orr, to photograph the rocks and letters. What emerges from Bad Luck, Hot Rocks is a feeling of bemusement, but also poignancy, revealing something about the subjective weight we are willing to assign to objects from the natural world. What this work does superbly is reflect the anxiety we have in regards to the environment, its power beyond us, our power to affect it, and the collective guilt that arises from that.

Thompson’s favourite letter from the series is one in which the author has simply written, ‘Sorry; For My Father’ in big letters. “I’m especially taken by the letters that reveal deeper truths or can be read in multiple ways,” he says. “This one could be a kid apologizing because his father told him to, or it could be a kid apologizing on behalf of his father. It could also be an adult son. In any case, we can also read it as a generational reckoning. We’re always apologizing for the misdeeds of our forebearers and attempting to make better mistakes.” In other words, it may start small—a single rock—but that impulse to control or own reverberates and grows, right up to the ways industry has depleted our natural resources.

“The entirety of Bad Luck, Hot Rocks is a metaphor for, and microcosm of, our larger neglect and abuse of the natural world,” Thompson says. “I love the redemptive impulse of returning a rock to a place from which it came. The confessional aspect of many of the letters reinforce this—with senders explicitly seeking forgiveness from either God or park staff. Whatever the impetus for the returns, I find the impulse beautiful, even if it’s ultimately a failure in a material sense.”

In another of Thompson’s series, Meteorwrongs, he photographs a series of rocks once identified as meteorites, but later proven to be of earthly origin. “For me, these photographs point to seismic shifts in our understanding of matter,” he says. “What’s wonderful about that revelation is that our understanding has shifted dramatically, but the rock itself is unchanged.”

In her book Wanderlust, the writer Rebecca Solnit wrote of the Native American Wintu people. Quoting Dorothy Lee, she explains, “when the Wintu goes up the river, the hills are to the west, the river to east; and a mosquito bites him on the west arm. When he returns, the hills are still to the west, but when he scratches his mosquito bite, he scratches his east arm.” This sort of directional, geological consciousness is rare, Solnit says—only really embedded in languages that are dwindling towards extinction—but it could hold the key to a radical mainstream rethinking of our relationship to the environment. “In Wintu, it’s the world that’s stable, yourself that’s contingent,” she concludes.

For American photographer Ron Jude, the same sort of probing of the “myth of human centrality”, as he calls it, was one of the primary impulses behind his new body of work, 12 Hz—a series that considers the invisible forces at work on landscapes through epic black and white photographs of lava and rocks, which he began in his home state of Oregon. Having moved there the year before this project began, Jude found himself struck by the diversity and power of the surrounding landscape.

“I’ve never had a desire to make pictures that were explicitly about the landscape, nor have my projects been driven by topical issues, but as I began looking at lava formations and tubes I started to see the potential for something that addressed the existential threat of the current political crisis, and how that dovetailed with things I was thinking about regarding humanity’s role on the planet. There’s an embedded element of concern about the environment in this work, but I like to think of these photographs less as lessons and more as reminders of scale and hierarchy.” As he sees it, the landscape is active, but also acted upon, and his pictures are something akin to “collected acts of witness and homage”.

Jude begins his project with a quote from Robinson Jeffers—“We must unhumanise our views a little, and become confident / As the rock and ocean that we were made from”—and in picking up on that later, he says, “with good reason, we all have a tendency to frame things with a human perspective. I thought that at this point in the medium’s history it could be interesting to attempt to make landscape photographs that didn’t engage in explicit critique, which I find to either be potentially condescending or one-dimensional and obvious. Of course, on the flip-side of that are images that idealize and mythologize the landscape and lack any real weight or tension. It’s a tricky problem.”

“The goal was to make work that reflected the indifference of nature, while not simply engaging in some sort of fantasy about the landscape. The earth is a complex system of fantastic phenomena that is often trivialized by sentimentalizing its surface appeal or reduced to victimhood through preaching-to-the-choir critiques of human behavior that have no real potential for correcting that behavior,” Jude explains. “My thinking around how I wanted this project to operate was that it should be a simple reminder of the causal chain of things happening on a scale that often operates outside our perception.”

While most of the projects included in this essay focus on one end of the scale spectrum, Claudia den Boer’s To Pick Up A Stone does both, moving deftly between images of mountains and the stones we unearth at the foot of them. She began picking up stones while working in and wandering through landscapes in countries including Tibet and the Sahara, and then at home, she photographed them as if they were mountains, zooming in close and playing with perspective.

“While doing that, I came to the conclusion that if I wanted to make a stone look like a mountain, I should be next to an actual mountain,” she says. “So I applied to an artist residency next to a mountain, took my stones with me, and photographed the surrounding landscape. I was captivated by the ever changing ‘faces’ of the mountain, how it kept changing in appearance.” Layering together these different images, she experimented with blending their forms into a rich visual experience, indistinguishable in scale and perception.

“In the end the meaning of the stones is not so much derived from the emotional story I have with them, but more as a way of trying to convey the value of the earth as a whole. Rocks and mountains have such a great primal force to them and that evokes a longing and a sense of belonging for me, and a strange feeling of reassurance. The earth, and the mountains existed long before we human beings did.” She likes the thought that in the grand scale of things, humans might not be that important, and takes pleasure in reflecting on the way we take up space in the world.

So, why photography, and why rocks? For Boer, “it has something to do with observing, and the intensity of the act of observing,” she says. “Photography might be my way to feel a deep connection with the landscape. I can look at it and be in awe, but when photographing it, the experience of feeling connected intensifies.” Elaborating on this shared impulse, Thompson raises the idea that the very nature of photography helps to create a productive tension when depicting rocks. “I tend to think of all photographs as slippery objects. Rocks are the opposite. The fact and fiction that feels simultaneously present in a photograph allows us to imagine alternative ways of being or conceiving while looking at images that feel like they belong in a natural history museum.”

For Jude, it’s a way to address the frustrations he feels towards the medium. “Photography is a language I both understand and simultaneously am vexed by. It’s an unsolvable problem and 12 Hz is just another experiment with the medium for me.” Working out how that translates to the way we experience the natural world, he says, was the real challenge. “On the one hand I was interested in taking the ‘human experience’ out of the equation and making work that attempted to be as oblique as it was translatable. This was a useful working premise, but in the end I realize that it’s an impossible paradox and that ultimately the photographs are meant to do something, to have a trace or legibility of experience, whether you call that ‘awe’ or the sublime or whatever. Ultimately, I was interested in a sense of power and scale, coupled with a sort of disorientation brought on by a disembodied viewpoint.”

Somehow, through silent images of seemingly static objects, each of the artists here bind human action to geological circumstance, in ways both direct and incidental, subtle and seismic. Variously experimenting with ways of intertwining and removing themselves from the landscape through the act of photography, they make it impossible for us to look away from the weight we place on the environment; holding the landscape back up to us like a mirror, and illuminating what we stand to lose if we continue to take it too far.