Since getting the “all clear” from her cancer diagnosis, photography has become a therapeutic tool for Australian photographer Lisa Murray. In her past two projects, she has developed a way to use her camera to process difficult, painful experiences in a multitude of powerful ways. From piecing together a linear story of her illness with the help of her child’s perspective to thinking about how our brains work to protect us from our own memories, Murray’s creative practice places healing at its center.

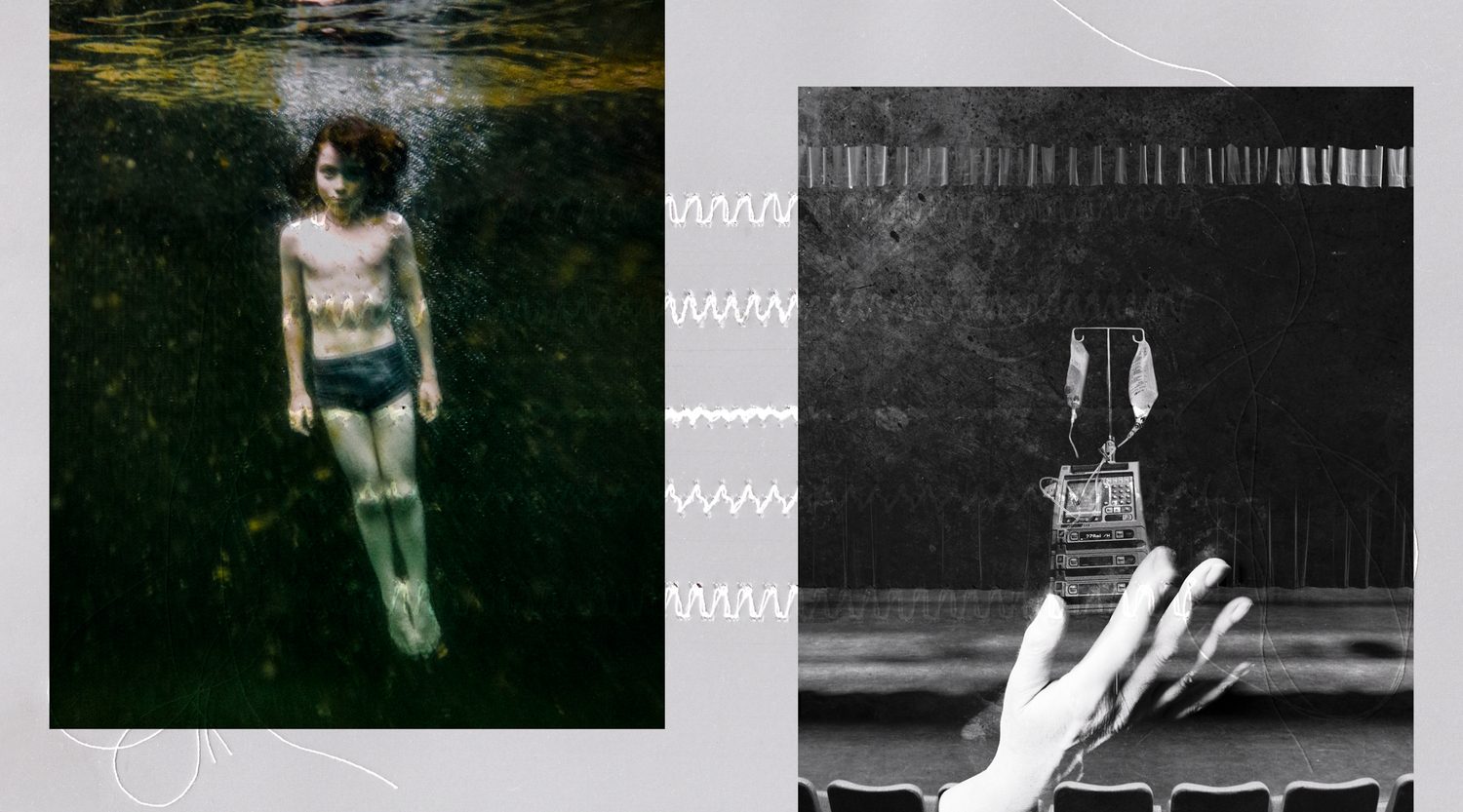

In her most recent series For Parts Not Working, she explores the somewhat-invisible wounds that came from a traumatic brain injury she experienced following a serious bike accident. Taking its name from the phrase used to list and sell a broken camera, this collection of photographs pays tribute to the inner workings of her “broken” mind. Comprising a variety of creative approaches — staged underwater scenes that excavate traumatic hidden memories, collage, sculptural work made by her children, and textiles whose stitched patterns gesture towards hospital vital monitors — Murray’s project explores the intelligence, resilience and vulnerability of the human body.

In this interview for LensCulture, she speaks to Sophie Wright about how photography became part of her recovery, the challenges of sharing her personal story and the guiding force of having an “art bestie.”

Sophie Wright: Can you tell me about your beginnings in photography? Do you remember the feeling you had that led you to pursue it?

Lisa Murray: It was in high school that I first started to notice visual narratives occurring in my world from a photographic point of view. I became an expert at forging my dad’s signature so that I could borrow the school’s Pentax loan camera. The darkroom became a safe haven where magic was created. I remember standing still until my eyes adjusted to the dark before knowing who was in there working on prints; it was a nervous rush, and I loved it!

I began a bachelor’s in photography at the ANU (Australian National University) in my early 20s. Back then, I was frustrated by the technicalities of photography—everything had to adhere to a clean, precise formula, and I just wanted to express myself, or create a mood. Dust included. It eventually put me off completing the degree. Ironically, I think I’ve spent most of my life trying to remember and adhere to the rules ever since. It’s so weird.

SW: How would you describe the things you want to explore as a photographer and how did these interests come your way? Why is photography the way you’ve chosen to speak about them?

LM: It all relates to memory and processing. I don’t remember anything clearly unless I’ve taken a photo. One of my children remembers places by what she ate there: for her, it’s food, for me, it’s photographs. I often trawl through the archives to create new images out of old ones to help me to process something I need to work through. It’s super accessible.

SW: Your work draws strongly on your own life experience. When did this autobiographical bent start shaping your practice? And what does it bring you to work with your own life as material?

LM: It began in lockdown. After getting the ‘all clear’ following my cancer-filled chapter of life, I was keen to create something tangible from the experience, to lay it all down in story form as a way to process what my family and I had gone through. Creating work in this way unjumbled a tangled mess of single, near-death experiences into a clean, linear format in my mind resulting in the series Through My Child’s Eyes.

SW: This gesture requires seeking possibility out of pain. Do you ever encounter challenges working in this way?

LM: Absolutely! Most of my series work was created struggling to see my screen through all the tears! But the flip side is I understand more about how my brain functions and know myself more deeply because of it. I’m more easily able to pull memories from that buried place, and after I create work, I can move on a lot faster; it’s such a beneficial process for me.

Sharing my story with the world in Through My Child’s Eyes was the most difficult thing, but in doing so, I connected with so many people. It humanized the experience and helped me to process so much of the related trauma. This experience led me to think: why not process more of the experiences my brain has cleverly dissociated from and hidden away? That was how For Parts Not Working was born. The series is really a therapeutic exercise, created as a tribute to my brain.

SW: Can you tell me about the accident that sparked For Parts Not Working? How did the experience unfold into a project?

LM: It happened on a downhill slope—my child put his feet through the spokes of our bicycle, and together we were thrown over the handlebars. My mothering instincts took hold, and I wrapped my arms around my baby, taking the impact of the pavement with my head. I woke in a stranger’s arms and later learned that my baby came away virtually unscathed.

I have a pretty substantial facial scar from the 45 stitches where my sunglasses and helmet strap went through my skin, but the hardest part was learning to live with the concussion I sustained due to the Traumatic Brain Injury. It made life so difficult as every process that had once come without a thought became so slow and difficult. Someone would ask me a question, and I could watch my brain decipher the bit of information within the question that sought an answer.

I’d need to interpret it and apply my own experience before being able to determine what to say back. I’d have to manually select the words, out of the endless possibilities of words in the world to choose from, and then finally place them in an order that was coherent to answer the question. By the time I got to speaking, I would just stutter as I couldn’t form the words. It was utterly exhausting for everyone.

SW: It seems like the work you had to do neurologically—diving into your memories and repatching them together, learning how to live with a concussion, being temporarily mute—had a great influence on your work process. Can you speak a little to how your condition shaped your approach? What did this process look like?

LM: The process of witnessing my brain functioning in this way has stayed with me. As time healed, I noticed the stutter was only present if I was talking about trauma, which is how I found the place in my mind which houses my life traumas. I have depicted this place in my series as being underwater. Once I was able to mentally open that case, I found my traumatic memories were all laid out there in chronological order—including some that I had completely blocked out. I began a long process of accessing one trauma at a time. I’d write the words first, and then create the accompanying visual to try and articulate it.

SW: There are several types of images threaded together in For Parts Not Working, gesturing towards the visible and invisible scars you are working through. Can you talk me through the different images we see, in particular the photographs taken in water?

LM: The place deep within my mind can only be visually articulated underwater. The person I photographed is intended as a metaphor for myself, and the case they are holding represents this self-created safe place I’ve housed my traumatic memories over the years to protect myself.

Some memories were just too horrible to be put out into the world in an obvious way, so I have tried to treat them in a more abstract, elusive way. It doesn’t really bother me if the viewer can’t interpret them.

SW: Can you elaborate on the multimedia elements of the project? What did extending past the photographic bring to the project?

LM: The mixed media element started with wanting to visually articulate a hospital vital signs monitor, as they are ever present in most of my traumatic memories. I was then able to use this template as a way of stitching together my two sides—the place the memory came from on the left, with what the memory was on the right.

So much of my experience of being a mother is wrapped up in being incredibly unwell. As a result, much of the artwork my children did when they were little perfectly articulates our shared lived experiences, and it seemed a natural progression to draw from this resource.

SW: Though your work is deeply personal, there seems to be a multitude of voices mingling together—who is speaking in the text that accompanies the images here?

LM: It’s different with every chapter. I say “chapter” because that’s how it’s cataloged in my mind, like a book of stories. The text speaks to the person in the chapter, sometimes myself, sometimes multiple me’s as I dissociate from the situation and watch myself in it. Funny how brains work—always on our side. They are very clever, really.

SW: Did you have any influences whilst making the project? Photographic or otherwise.

LM: This work is all about trying to articulate and shift the stories I see in my head, and I don’t believe I thought about much else while I was creating it, to be honest. That said, I have an artist bestie—Arrayah Loynd, who is also a LensCulture Emerging Talent winner. The two of us talk on a daily basis and aren’t afraid to offer each other constructive feedback.

We rarely put work out into the world before presenting it to each other first. Our brains seem to work in a similar way and running my artwork past her is like having my own opinion mirrored back at me but without being clouded by the creative fatigue that comes from making it. It’s an unbelievably useful exchange. I liken it to having a mentor and value it very much.

SW: As you’ve mentioned earlier on in this conversation, you’ve worked with illness in your practice before. Is there anything you brought from your past experience to this project?

LM: I knew, from my first series, that delving into this trauma would help me to process some of the things I’ve been through that my brain has dissociated from in order to survive. I knew I would feel lighter mentally for having done it. I also knew I was likely to want to hide under a rock the moment I hit “send’”on my LensCulture submission and my work went out into the world. It’s a very exposing and raw space to place yourself in but knowing from experience that these feelings would pass, and that the benefits would outweigh any pain allowed me to step back and just breathe for a while.

SW: In looking at the images, stitched and sutured together, it seems like you have repaired something. Do you see photography as a tool for healing?

SW: Photography, for me, is undoubtedly a healing tool. My husband swears by meditation, but for me, it’s creating an image that unscrambles my thoughts, provides mental space, and leaves me feeling centered and calm.

Lisa Murray is one of 25 remarkable photographers we discovered through the LensCulture Emerging Talent Awards 2023.