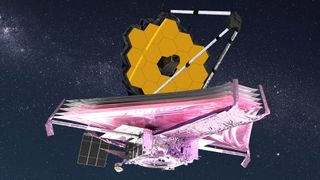

How to watch the James Webb telescope launch into space

It will be the biggest and most powerful telescope ever launched.

UPDATE: This article was updated Dec. 22 to reflect the telescope's new target launch date of Dec. 25. NASA will confirm the new date on the evening of Dec. 22, agency representatives said in a statement, check back here at Live Science for more updates.

On Saturday (Dec. 25) between 7:20 a.m. and 7:52 a.m. EST, a shiny new observatory called the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is scheduled to ride a rocket launching from South America. Once aloft, the space telescope will take its place in orbit as humanity's newest and most powerful eye in the sky, scanning the cosmos for signs of the earliest galaxies, newborn and ancient stars, and even life in distant solar systems.

The launch was previously scheduled for Christmas Eve (Dec. 24), but on Tuesday (Dec. 21), NASA representatives announced in a statement that the launch would be postponed due to adverse weather conditions.

Related: Building the James Webb Space Telescope (photos)

Live launch coverage in English begins on Dec. 25 at 6 a.m. EST. You can watch the launch here at Live Science, on NASA's YouTube channel and NASA TV, and on the agency's website and social media accounts. Spanish language coverage will begin at 6:30 a.m. EST on the NASA en español's YouTube account and on NASA's website, NASA representatives said on Saturday (Dec. 18) in a statement.

You can also check in at our sister site Space.com all week, to catch the latest updates leading up to the Dec. 25 launch.

The JWST mission is expected to last five to 10 years and is an international partnership between NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA). Carrying the telescope is an Ariane 5 rocket, which will launch from the Guiana Space Centre — also known as Europe's Spaceport — to the northwest of Kourou in French Guiana, ESA representatives said in a statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Like its predecessor the Hubble Space Telescope, which launched on April 24, 1990 and is still active, JWST will observe cosmic objects to help astronomers answer questions about the formation of the universe. Over the past 30 years, Hubble has captured breathtaking images of planets, stellar nurseries, colorful nebulas and clusters of galaxies spanning billions of light-years.

But while Hubble conducted most of its observations in ultraviolet (UV) and optical wavelengths, JWST will mostly operate in infrared (though it has instruments capable of observing across a range of wavelengths). JWST also has a much larger mirror than Hubble does, which will capture more light. Both of these upgrades will provide a more detailed view than Hubble could, of the universe's earliest objects.

A million miles away

After JWST leaves Earth, its new address will be "L2," a destination nearly a million miles from its home planet, according to NASA. The abbreviation refers to the second Lagrange Point; there are five of these points in our solar system, and they represent "a wonderful accident of gravity and orbital mechanics," according to NASA. At each Lagrange Point, the gravitational pull of Earth and the sun match the centrifugal force of smaller orbiting bodies, so a satellite can be "parked" in a stable spot where it won't need to expend much fuel to stay in a fixed position.

For JWST, that spot is located in the opposite direction from the sun, approximately 930,000 miles (1,500,000 kilometers) from Earth.

The L2 position is especially good for this new telescope. As JWST will be looking at objects in space using infrared, being as far away from the sun as possible will help the telescope to spot very dim, distant objects. And because the telescope will live at a fixed address, NASA can establish continuous communication with it through the Deep Space Network. This array of giant radio antennas is scattered across three facilities that are separated from each other by 120 degrees longitude, so that the array can maintain contact with satellites and interplanetary missions as Earth rotates, according to NASA.

However, sending JWST to a spot that's so far away also means that astronauts won't be able to visit and fix the telescope should it require repairs, as they could do with Hubble. Hubble orbited Earth at a distance of about 340 miles (547 km) and was built to be easily serviced; every piece of Hubble hardware had a backup installed in case of failure, and NASA conducted five repair missions between 1993 and 2009 — but that option simply won't be possible for JWST.

"In the early days of the Webb project, studies were conducted to evaluate the benefits, practicality and cost of servicing Webb either by human space flight, by robotic missions, or by some combination such as retrieval to low-Earth orbit," mission representatives said in a statement. "Those studies concluded that the potential benefits of servicing do not offset the increases in mission complexity, mass and cost that would be required to make Webb serviceable, or to conduct the servicing mission itself."

If all goes well, JWST will will deploy the sun shield after about a week in space, and will reach its new address and begin orbit insertion within a month, according to NASA. After that, mission engineers will remotely align and calibrate the telescope's instruments, and it will perform its first observations after six months.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.